From an accounting perspective, fixed assets – an item with a useful life greater than one reporting period, depreciated over time. Fixed assets are also known as capital assets and tangible assets. These are items that an organization purchases for long-term business purposes. This is not inventory that business is planning to resell to make a profit, but rather an investment.

The cost of those items is spread out over multiple years, and it wants to track those items on the balance sheet. The way one would track a fixed asset on the balance sheet is by using an Accumulated Depreciation expense account.

The main advantage of spreading out the cost of fixed assets is the amount of taxes you will pay because the company will lower its taxable income. It also helps you to ensure that your income is not understated when you make a large purchase and not overstated in the following years.

Fixed Asset Accounting Life Cycle

All fixed assets go through the same life cycle:

- Acquisition: a new fixed asset is entered into an entity’s books.

- Depreciation/Amortization: a periodic decline in value calculated to reflect the age and wear and tear on fixed assets.

- Revaluation: a periodic assessment of a fixed asset to record its current fair market value. The value may go up or down.

- Impairment: a recorded reduction in the value of a fixed asset because of events or circumstances.

- Disposition: the selling, scrapping, or another form of disposing of an asset at the end of its service life.

Fixed Assets vs. Current Assets

The concept of fixed and current assets is simple to understand. The short explanation is that if it is an asset and is either in cash or likely to be converted into cash within the next 12 months (or accounting period), it is considered a current asset. Fixed assets, on the other hand, as we said above, are not going to be sold within the next 12 months.

Let’s say you have a delivery truck. If your business consists of buying and selling trucks, then it will be considered a current asset. However, if you are using it to deliver products to your clients, then it will be a fixed or non-current asset.

Depreciation Methods

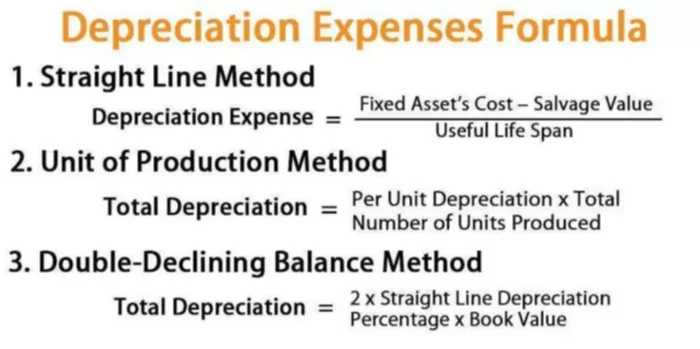

It is important to point out that there are various depreciation methods that an organization can use to calculate depreciation expense. There are three common methods:

- Straight-line – an equal amount of depreciation is applied every year for the asset’s useful life;

- Double declining balance – an accelerated depreciation, where this expense is greater in the first few years and smaller in the later years, which allows companies to have smaller tax bills in the beginning;

- Units of production – the depreciation expense varies each year because it is based on the output produced by the assets. This allows the company to match the actual output to the depreciation expense that it incurs.

Fixed Asset Depreciation Example

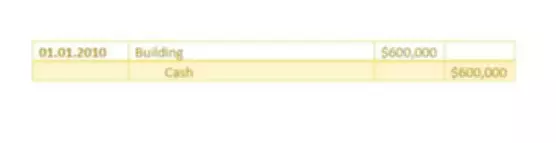

Let’s say you buy a building for $450,000 and spend another $150,000 to make it ready to use as a restaurant. In total, you pay the $600,000 on the date you open the restaurant, which is 01.01.2010. The building’s value is equal to whatever it took to make it ready to use, for example, upgrading the plumbing and electric. Thus, you will make the following entry.

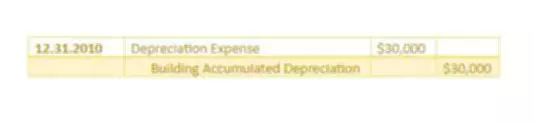

You will depreciate the building over 20 years with zero salvage value using the straight-line depreciation method. So, each year your depreciation will equal $600,000/20 = $30,000.

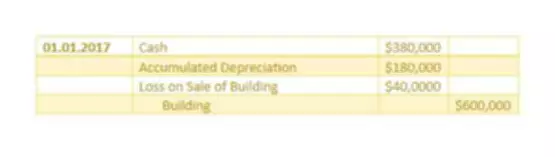

If you decide to sell the building on January 1st, 2017 and receive $380,000 for it. You have depreciated it for five years so that the total Accumulated Depreciation account will show $180,000. The book value of your building is then $600,000 – $150,000 = $420,000. Thus, if you sold your building for $380,000 and your book value is $420,000, then you have a loss on sale equal to $40,000. This will be recorded as follows:

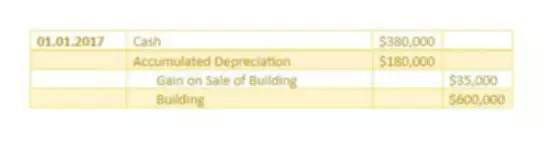

If you sell, let’s say for $455,000 instead of $380,000, you will have a gain equal to $35,000, which will be reflected in your books as follows: